The land that makes up Israel and Palestine has been inhabited—and contested—by human beings for nearly two million years. The Holy Land is not only the cradle of Judaism and Christianity; it is incredibly sacred to both Muslims and people of the Baha’i faith. In its history, the land has seen a variety of empires, kingdoms, and peoples, including Egyptians and Canaanites, Israelites and Philistines, Greeks and Judeans, Romans and Byzantines, Arabs and Crusaders, Mongols, Ottomans, and British.

Israel, located just east of the Mediterranean Sea, is the world’s only Jewish state. Palestinians—the Arab population from the land Israel now controls—refer to the territory as Palestine and want to establish a state by that name on all or part of the same land. Both Jews and Arab Muslims’ claims to the land date back a couple of thousand years; thus, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is primarily a conflict over who gets what land and how it’s controlled—a conflict over territory. This conflict is disputed primarily between two different groups: Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs, who are chiefly Muslim but also include Christians and Druze.

Where Do We Start?

Due to the long and complicated history of this land, this article will only scratch the surface of the current Israeli-Palestinian political conflict—providing a very brief history that is largely based on the late 19th through the 21st centuries.

Leading Up to 1948

In the late 19th and into the 20th century, large numbers of Jews immigrated to Palestine from Russia, Yemen, and other countries. At the time, the land of Palestine had been under the control of the Ottomans for nearly 400 years. A great number of these Jewish immigrants were followers of Zionism—a movement that created and supports Israel as the official state for Jewish people in Palestine, developed largely in response to post-Napoleonic nationalism in Western Europe and the development of pogroms in Eastern Europe. The year 1882 marks the first large Zionist immigration to Palestine, known as the ‘First Aliya.’ This was followed by the Second Aliya in 1903.

In 1917, the British government issued the Balfour declaration that stated that “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish People,” then proceeded to capture Jerusalem and northern Palestine from the Ottomans. After the end of WWI, Jews resumed immigrating to Palestine to territories now controlled by the British-run mandatory government. This was followed by the Third (1919-23), Fourth (1924-29), and Fifth Aliyah (the 1930s). The last of which was largely made up of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. This rise in Jewish immigration angered Palestinian Arabs, who began to see a growing Jewish population as a threat to Arab interests.

This led to the Arab Revolt (1936-1940), which protested Zionism, Jewish immigration, and policies of the British Mandate. This revolt resulted in the death of about 400 Jewish civilians, 200 British soldiers, and 5000 Palestinian Arabs, who were suppressed by the Mandatory government. One result of the Revolt was that the British severely limited Jewish immigration to Palestine. This occurred just as the Jews of Europe were desperately trying to flee Hitler and Nazism. Even after WWII, the British prevented Holocaust survivors from reaching Palestine, but many Zionists continued to smuggle refugees into Palestine.

In 1947 the British government, exhausted by both WWII and Arab and Jewish violence in Palestine, passed the Palestine situation onto the two-year-old United Nations to deal with. The United States, Soviet Union, and United Nations General Assembly voted to partition Palestine into two independent states: one Arab; one Jewish. While the Jewish Zionists agreed to this plan, in theory, the Palestinian Arabs and nearby Arab countries did not and began attacking Jewish targets. As soon as the British left in May 1948, the Jews proclaimed the establishment of an independent Jewish state, and the armies of Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq invaded Palestine—resulting in war and violence in the region.

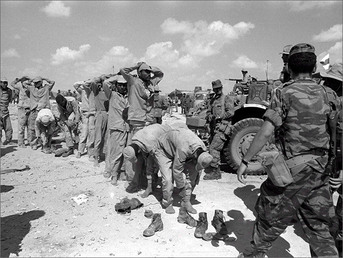

1948: Arab-Israeli War and Israeli Independence

To the surprise of the Arab world, the 650,000 Jews were not defeated by the five Arab armies and instead took control of 77% of Palestine; originally the UN Partition Plan had offered them 56%. This solidified Israel as an independent state and a refuge for Holocaust survivors and Jews facing persecution around the world. For Palestinian Arabs and the Arab world, this turn of events was a catastrophe. Roughly 700,000 Arabs living in what was to become Israel were expelled by the end of the year.

This moment in the conflict has lasting effects to this day, as it resulted in humanitarian disaster and the unresolved issue of Palestinian refugees that exists to this day. In fact, at the close of 1948, over 80% of Palestinians had become refugees. As Israel established itself as an independent state, Jews from around the world began flooding into the region. Within three years, Israel’s Jewish population more than doubled.

1967: The Six Day War

In the spring of 1967, Arab capitals in the region sought to liberate all of historic Palestine in the name of pan-Arab nationalism—viewing the occupation of Palestine by Israel as illegitimate. President of Egypt Gamal Abdel Nasser made speeches to the Arab world, declaring that their objective was “the destruction of Israel,” and Jordan and Syria massed troops on their borders with Israel.

Israel took this threat seriously and launched a preemptive attack against the surrounding Arab forces of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. In less than a week, Israel was victorious and had more than tripled its territory—capturing the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan, the Golan Height from Syria, and Sinai and Gaza from Egypt. Many Israelis viewed this victory as nothing short of divine intervention, which affirmed their beliefs regarding Jewish control of the land.

1970s: War and “Peace” with Egypt

In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar: Yom Kippur. Both Arab and Jewish sides experienced high numbers of casualties; however, Egypt was able to portray the Yom Kippur War or October War as a victory. Israel came to realize that they would not always be able to dominate Arab armies in the region, as they had done previously. This change in mindset paved the way for the subsequent peace process.

In 1977, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat traveled to Jerusalem and offered to make peace with Israel in return for withdrawal from Sinai and the promise of progress towards Palestinian autonomy—the latter of which was never fulfilled. This agreement between Israel and Egypt, known as the Camp David Accords, was signed in 1978. Israel completed its evacuation of Sinai in spring 1982, which included 7000 Jewish settlers.

1982: The Invasion of Lebanon

In 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon and besieged Beirut after tensions rose between the Lebanon-based Palestine Liberation Organization forces and Israel. The objective was to drive the PLO out of Lebanon and to install a pro-Israel Christian government. Yasser Arafat and PLO fighters eventually left Beirut by sea and transferred their headquarters to Tunis.

Many Israelis opposed the war in Lebanon—feeling that it had been launched without proper government approval and that it further tainted Israel as a country, specifically when Christian Lebanese allies massacred Palestinian refugees in the Beirut camps of Sabra and Shatila in 1982 as IDF soldiers looked on. While all of this was happening, Palestinian refugees in the West Bank and Gaza, in refugee camps in neighboring countries, and across the Arab world waited for a solution to their displacement and plight.

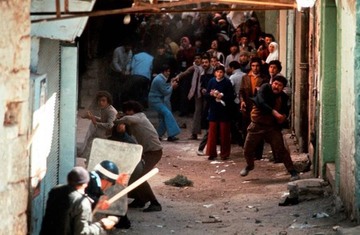

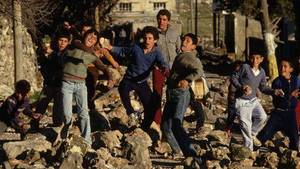

1987-1993: The First Intifada

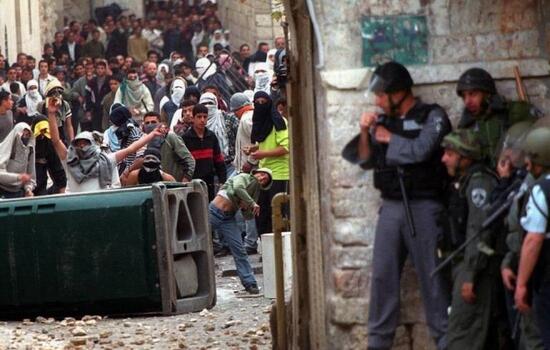

In 1987, a popular uprising against Israeli occupation arose in the West Bank and Gaza, where the majority of Palestinians were based. This became known as the First Intifada, or “shaking off,” which was characterized by resistance in the form of strikes, stones, and Molotov cocktails.

Arafat, based in Tunis, soon took control of these Palestinian territories and garnered worldwide sympathy for the Palestinian cause and international condemnation of Israel. In 1988, Arafat renounced terrorism and effectively-recognized Israel, which paved the way for the Oslo Accords of 1994.

The Oslo Accords

In 1993, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO Chairperson Yasser Arafat signed the Oslo Accords, in which Israel would hand over control of territory to the Palestinians in stages, beginning with the major towns of the West Bank and Gaza. The future of Jerusalem and Palestinian refugees’ right of return were to be negotiated after a five-year interim period. These issues have yet to be discussed. In short, the Oslo Accords were based on the two-state solution proposed by the UN in 1947.

In 1994, Arafat arrived in Gaza to head the new Palestinian Authority established by the Accords. Over the next few years, Israel returned some of the lands in Gaza and the West Bank to Palestinians; however, the situation is extremely complicated and the Palestinian territories remain divided and under Israeli military control to this day. Ultimately, the Oslo Accords did not lead to peace; rather, they drove extremists on both sides to greater acts of violence. For more information about this, the Oslo Accords, and the PA, please read our article “What is the Palestinian Authority?”

Post-Oslo Signing

Following the Oslo Accords, violence swept the region. Hamas and Islamic Jihad began suicide bombing against Israeli Civilians, and Israel began assassinating Hamas and Islamic Jihad leaders, which resulted in civilian casualties. Military presence and settler violence against Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza increased, and Palestinians faced heavy restrictions on movement and a depressed economy under Israeli occupation.

In 1995, Prime Minister Rabin, who signed the Oslo Accords, was assassinated at a Peace Rally by a right-wing Orthodox Israeli who—along with his fellow nationalist Israelis and especially Jewish settlers—bitterly opposed Rabin’s agreement to give up part of the historic ‘Land of Israel.’ Allowing Palestinians to have even a small portion of Israel’s God-given birthright was considered a great crime. Violence on both sides continued.

2000-2005: The Second Intifada

In 1999, a center-left coalition led by Ehud Barak took office. Barak and Arafat agreed to a summit with Bill Clinton with the aim of striking a final peace deal. Negotiations failed and widespread violence broke out, developing into the Second Intifada. Young leaders of Arafat’s Fatah party rebelled against Arafat and allied with Hamas and Islamic Jihad to launch a wave of suicide bombings.

In 2001, Ariel Sharon was elected Prime Minister. Sharon opposed Barak’s efforts to strike a deal with Arafat, sent tanks to occupy West Bank towns that had previously been ceded to Arafat, made bloody incursions into Gaza on a frequent basis, and carried out ‘targeted assassinations’ of presumed terrorist leaders. He also confined Arafat to a compound in Ramallah, where he grew sick and later died while receiving treatment in France in 2004.

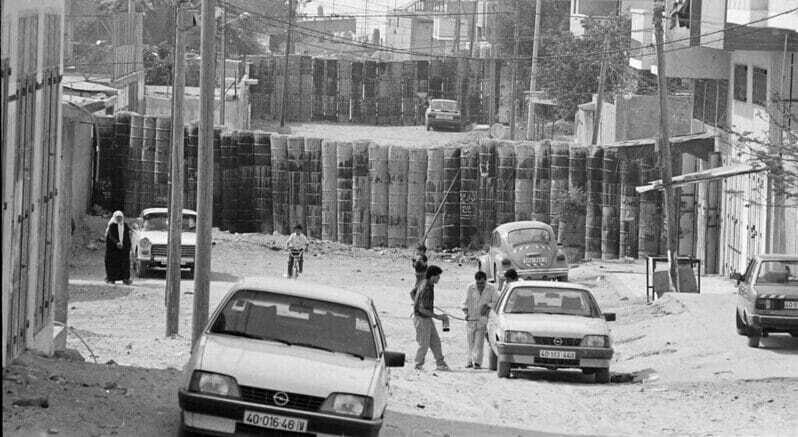

Over the course of the Second Intifada, more than 1000 Israelis died, 70% of which were civilians, and roughly 4700 Palestinians died, more than 2000 of which were civilians, according to human rights group B’Tselem. With Arafat dead, Sharon took to a policy of disengaging with Palestinians—building the Separation Fence or “Apartheid Wall” around much of the West Bank and pulling out of isolated settlements. This evacuation included some 8600 Israeli settlers in the Gaza Strip and four settlements in the northern West Bank. Zionist settlers are outraged and radicalized by this withdrawal from what they believe to be their ‘God-given Land of Israel.’

Hamas and the PA

In 2006, Hamas won the Palestinian parliamentary elections. This led to a split in the governance of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, with Hamas controlling Gaza and the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority controlling the West Bank.

The Gaza Strip was taken over by Hamas by force and many Fatah officials who were unable to flee were tortured and killed.

Recent History

At the end of 2008, Israel launched an offensive to stop missile attacks coming from Hamas in Gaza. This three-week offensive left much of Gaza’s infrastructure in ruins and thousands homeless. According to B’Tselem, 1397 Palestinians and 5 Israeli soldiers were killed. Despite this, Hamas remains in power in Gaza.

In 2013, US-sponsored Israeli-Palestinian peace talks began and quickly collapsed, due in part to the continued construction of illegal settlements in the West Bank under Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu.

In 2014, Fatah and Hamas attempted to establish a government of national unity, but it has been largely ineffective as differences and mistrust between the two groups remain strong. Furthermore, the Hamas-Israel war broke out in June 2014 after three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped and murdered by Palestinians. Israel carried out raids and arrested hundreds, and rockets were fired back and forth between Israel and Gaza. This 50-day war left more than 2100 Palestinians dead, 69% of which were civilians according to the UN; and 73 Israelis dead, 67 of them soldiers. Additionally, large parts of the Gaza Strip were left in ruins, including 17,200 homes, and hundreds of thousands of civilians were left traumatized.

Now

There does not seem to be an end in sight for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Much of the recent peace efforts have been rooted in a two-state solution; however, there are many barriers preventing real peace from being achieved. These barriers include extremist violence perpetuated from both sides of the conflict; the continued construction of illegal settlements in the West Bank; Israeli military occupation and mistreatment of Palestinian civilians; unresolved issues like control of Jerusalem and Palestinian refugees’ right to return; and lack of support for peace across the political spectrum in both countries.